The spring sun is warm on your back as you plant your feet into the starting blocks.

The snug fit of your track spikes keeps you grounded—you feel calm, but there's a buzzing energy just beneath the surface, waiting for the moment to explode.

Set!

Your body raises into position; every muscle and every tendon is prepared. You're a statue of focus, not a twitch or a flinch. The only thing that will unleash your energy is the sound of the starter's gun.

Bang!

The starter's pistol cracks the air, and in that instant, the calm energy coursing through your veins explodes into motion.

Your front leg drives you out of the blocks with immense power.

You don’t rush this step. You allow your leg to fully push, achieving triple extension. Feel your ankle, knee, and hip firing in coordination for maximum thrust.

Your back foot moves fast and low and your first step lands underneath your hip as you build speed.

It's the first step of many, but you've executed it flawlessly.

Welcome to the world of mental practice, a technique studied and validated over the past fifty years that's proven to help you prepare for a track meet.

Mastering this skill can dramatically improve your performance.

This technique works across the board—whether you're throwing the discus or running the 1500 meters.

And the more you practice mentally, the better you’ll perform.

Why Mental Practice is Especially Crucial to Prepare for a Track Meet

In sports like soccer or basketball, athletes can spend 30 minutes or more actively participating in a game. This gives players ample time to find their rhythm and correct mistakes.

Track and field athletes don't have that luxury.

Most events demand instantaneous performance. Sprinting and field events are over in seconds.

With such limited competition time, there's little room for error and no second chances to get it right during that attempt.

This high-stakes environment makes mental practice (MP) especially valuable.

It allows athletes to mentally rehearse their events many times, ensuring they are well-prepared and confident when it really counts.

Turning Downtime Into A Competitive Advantage

Let's face it: track and field involves a lot of waiting.

It's something you learn at your very first track meet.

And honestly, it doesn't really change as you progress in your career, whether you're competing in college or even the pro level.

Sprinters hang around for their heat; shot putters wait for their flight, and then their turn.

It's just the nature of the sport.

However, downtime isn't just about hanging out and checking your phone or getting caught up watching other competitors.

It's an opportunity. Mental practice is a tool that lets athletes shake off any setbacks from earlier attempts and stay fully engaged.

Mental practice can transform these stretches of waiting into crucial moments of preparation.

And this preparation can mean the difference between a decent performance and a PR.

Practice without practicing

Track and field is notoriously hard on the body.

Take the triple jump or long jump, for example. You might be able to get 6-8 all out efforts in.

The same goes for block starts; after about 6 reps, fatigue sets in, and performance goes downhill.

This is where mental practice offers a significant advantage.

Since it involves no physical exertion athletes can continuously refine their technique without the wear and tear.

Another benefit of MP is that it gives track and field athletes the ability to mentally slow down time, allowing them to deeply focus on the finer technical details of their event that normally fly by in fractions of a second.

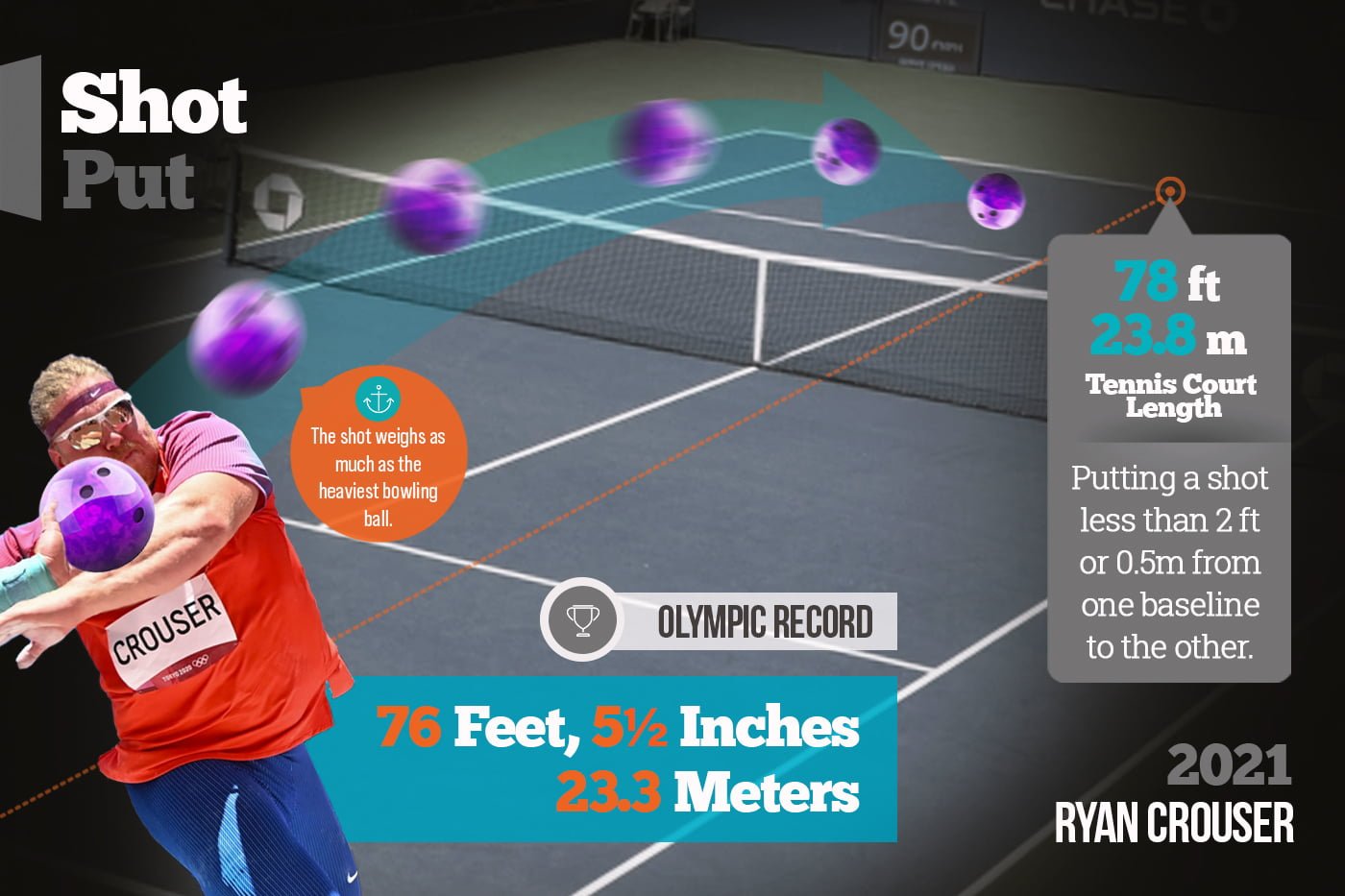

For instance, there are at least ten focus points to consider during a shot put stand throw.

It would be impossible to think through these points while throwing, especially during the speed of a full throw.

Athletes can use mental practice to focus on these details, refine their movements, and fix inefficiencies to significantly improve their performance.

How does Mental Practice actually work?

Mental practice uses a powerful, yet simple principle: when you visualize an action, your brain activates the same neural circuits as it does when you perform that action.

So the more you practice mentally, the stronger these neural connections become.

Ultimately this enhances the brain's ability to activate these circuits during physical performance.

For instance, a 2005 study by Lacourse et al., using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), showed that similar brain regions are activated during both actual and imagined hand movements.

The findings indicate that the more you practice mentally, the stronger these neural connections become, enhancing the brain's ability to activate these circuits during physical performance.

Similarly, a 2003 study by Jackson et al. used PET scans to examine changes in brain function after learning foot movement sequences through mental practice.

The study found enhanced activation in specific brain areas, demonstrating that mental practice not only simulates physical execution but also facilitates the brain's reorganization, improving both learning and performance capabilities.

Research has also demonstrated that the more vivid the preparation, the more effective it is.

For track and field athletes, this means visualizing every detail of their performance.

From the perfect block start, to their stride pattern, and even the tactile sensation of the track beneath their spikes. All of these details can effectively prime their muscles and neural pathways for the race.

In addition to the neural benefits demonstrated by Lacourse et al. and Jackson et al., recent research by Predoiu et al. in 2020 shows the broader psychological impacts of visualization techniques.

"Mental practice significantly boosts self-confidence, enhances attention, and improves performance under stress."

This study highlights that effective visualization goes beyond improving motor skills and muscle strength; it also significantly boosts self-confidence, enhances attention, and improves performance under stress.

Effective visualization engages multiple senses and incorporates both cognitive and emotional elements, making it a holistic approach that addresses both the physical and psychological aspects of preparing for a track meet.

How to prepare for a track meet with mental practice

The good news is that mental practice doesn't come with strict rules that athletes must follow to reap the benefits.

Even dedicating just a few minutes each day to mental rehearsal can yield results.

To help you start on the right foot and maximize the effectiveness of your mental practice, here are some general guidelines tailored to enhance your training and prepare for a track meet.

Regular Practice

Athletes should add mental practice into their daily training routines.

This process can be as simple as setting aside a few minutes each day to visualize their performance, focusing on the details of each movement and sequence involved in their specific event.

By doing so, mental practice becomes as routine as taping a wrist or putting on spikes.

This way, on meet day, there's nothing unusually different or special required. It’s simply part of their regular track meet preparation, which can enhance performance and reduce anxiety.

Detailed Visualization

Athletes should visualize the actions as well as the sensory experiences associated with their events.

Start with simpler, more general visualizations and gradually introduce more complexity and detail as the athlete becomes more comfortable and proficient with the technique.

A progressive approach helps build a stronger and more precise neural representation of the movements.

When adding detail, the more specific, the better.

For sprinters, this includes visualizing the feel of the track under their spikes and the sensation of wearing their racing jersey.

For discus throwers, it could be the texture of the ring, the feel of the chalk on their fingers, and the weight of the discus in their hand.

High jumpers could start with visualizing measuring out their approach, placing the tape on the apron, how the mat feels one their back.

These details help to prime the brain for more complex imagery like the sequence of movements they need to execute for the perfect high jump approach.

This detailed visualization helps in activating the relevant neural circuits as effectively as physical practice. The more detail the better.

Use of Video and First-person Perspective

To enhance the effectiveness of mental rehearsals, athletes should utilize video recordings of both their own performances and those of ideal models.

Choosing a model athlete with a similar body type can be particularly beneficial—for instance, a 5'8" sprinter might find more practical value in studying Christian Coleman than Usain Bolt, due to the closer match in physique.

Watching these videos before engaging in mental practice helps athletes visualize and emulate correct techniques more accurately.

Additionally, adopting a first-person perspective during mental imagery can further strengthen motor representations, making the mental rehearsal feel more real and applicable.

Maximizing Mental Practice

To maximize the benefits of training combine mental rehearsal with physical practice.

This integrated approach typically begins with a session of mental practice after the athlete has completed a proper warm up routine for track and field.

During the mental rehearsal, athletes should focus on visualizing each step of their performance, from the initial stance to the execution of technical skills (with the detail mentioned above).

This mental preparation helps prime the nervous system, setting a cognitive blueprint that can enhance motor performance.

Following the mental rehearsal, athletes should immediately engage in physical practice, executing the movements they've just visualized.

This combination not only reinforces the motor skills but also strengthens the neural pathways involved in the skill execution.

Research has demonstrated that this dual approach is more effective than practicing either technique alone, as it leads to improvements in both psychological readiness and physical performance.

Applying the Science of Winning

The role of mental practice in track and field cannot be overstated.

The evidence is clear: mental rehearsal is more than just a supplementary exercise—it's a crucial part of training that prepares athletes to perform at their peak when it counts.

It's an essential tool to prepare for a track meet.

As we've seen, the visualization and mental rehearsal techniques are supported by decades of scientific research, demonstrating their effectiveness in enhancing both physical execution and mental readiness.

For coaches and athletes alike, embracing these mental practice techniques will provide a significant edge in the highly competitive world of track and field.

Remember, success isn't just achieved on the track—it's also forged in the mind.

To truly harness the full potential of mental practice, understanding the correct techniques is crucial.

You don't want to mentally reinforce bad habits and poor technique.

Effective mental rehearsal relies not only on the consistency of practice but also on the quality of the imagery and the accuracy of the techniques envisioned.

If you want to deepen your understanding of technique and ensure you're getting the most out of mental practice, we invite you to explore our track and field courses taught by the most effective coaches in the sport.

References

Lacourse MG, Orr EL, Cramer SC, Cohen MJ. Brain activation during execution and motor imagery of novel and skilled sequential hand movements. Neuroimage. 2005 Sep;27(3):505-19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.025. PMID: 16046149.

Predoiu, Radu & Predoiu, Alexandra & Mitrache, Georgeta & Firanescu, Madalina & Cosma, Germina & Dinuta, Gheorghe & Bucuroiu, Razvan. (2020). Visualisation techniques in sport - the mental road map for success. 59. 245-256. 10.35189/dpeskj.2020.59.3.4.

Predoiu, Radu & Predoiu, Alexandra & Mitrache, Georgeta & Firanescu, Madalina & Cosma, Germina & Dinuta, Gheorghe & Bucuroiu, Razvan. (2020). Visualisation techniques in sport - the mental road map for success. 59. 245-256. 10.35189/dpeskj.2020.59.3.4.

Toth, A. J., McNeill, E., Hayes, K., Moran, A. P., & Campbell, M. (2020). Does mental practice still enhance performance? A 24-year follow-up and meta-analytic replication and extension. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 48, 101672.